Humanizmi dhe Renesansa

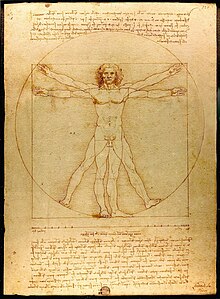

Humanizmi dhe Renesansa ose Humanizmi i Rilindjes është një lëvizje e studimit të shumanshëm të antikitetit klasik, fillimisht në Itali e pastaj edhe në vendet tjera evropiane, në shekujt XIV, XV dhe XVI. Termi Humanizëm është i kohës bashkëkohore me të cilin përcatohet ajo periudhë, ndërsa Humanizmi i Rilindjes ose Humanizmi dhe Renesansa është një retronim i përdorur për ta dalluar atë periudhë nga zhvillimet e mëvonshme humaniste. [1] [2]

Humanizmi dhe Renesansa ishte një lëvizje e reformimit intelektual, kulturor dhe arsimor në Evropën e periudhës së Mesjetës së vonë dhe periudhës së hershme moderne. Në këtë lëvizje ishin të angazhuar zyrtarë qytetarë dhe kishtarë, koleksionistë librash, mësimdhënës dhe shkrimtarë, të cilët në fund të shekullit XV filluan të quheshin "humanistë" - umanisti. [3] Më konkretisht ajo u zhvillua gjatë shekullit XIV dhe fillimit të shekullit XV dhe ishte një përgjigje ndaj sfidës së arsimit universitar mesjetar skolastik, i cili pastaj u dominua nga filozofia dhe logjika aristoteliane. Skolasticizmi u përqendrua në përgatitjen e njerëzve për të qenë doktorë, avokatë ose teologë profesionistë dhe bëhej mbi bazën e disa teksteve të aprovuara të logjikës, filozofisë natyrore, mjekësisë, ligjit dhe teologjisë.[4] Qendrat më të rëndësishme të humanizmit ishin Firenca, Napoli, Roma, Venediku (Venecia), Mantova, Ferrara dhe Urbino. Historiani gjerman i shekullit XIX, Georg Voigt (1827-1891) e identifikoi Francesco Petrarkën si humanistin e parë të Rilindjes. Paul Johnson pajtohet se Petrarku ishte i pari që thoshte se "shekujt midis rënies së Romës dhe të tashmes ishin epokë e errësirës". Sipas Petrarkut, ajo që nevojitej për të korrigjuar këtë situatë ishte studimi dhe imitimi i kujdesshëm i autorëve të mëdhenj klasikë. Për Petrarkën dhe Boccaccion, mjeshtri më i madh ishte Ciceroni, proza e të cilit u bë model i prozës së latinishtës së mësuar dhe të gjuhës italiane.

Humanizmi i Rilindjes ishte gjithashtu një reagim kundër qasjes utilitariste dhe pedantërisë së ngushtë që shoqërohej me të. Ata kërkonin të krijonin një qytetari (shpesh duke përfshirë edhe gratë) të aftë për të folur dhe shkruar me elokuencë dhe qartësi dhe në këtë mënyrë të aftë për t'u angazhuar jetën qytetare të komuniteteve të tyre dhe për t'i bindur të tjerët në veprime të virtytshme dhe të kujdesshme. Kjo duhej të realizohej përmes studimit të shkencave humanitare (studia humanitatis): gramatika, retorika, historia, poezia dhe filozofia morale. [5] [6] Si një program për ringjalljen e trashëgimisë kulturore - sidomos asaj letrare - dhe filozofisë morale të antikitetit klasik, humanizmi ishte një mënyrë kulturore gjithpërfshirëse dhe jo program i disa gjenive të izoluar si François Rabelais ose Erasmo Roterdami, siç cilësohet ndonjëherë.[7]

Shih edhe[Redakto | Redakto nëpërmjet kodit]

Linqe të jashtme[Redakto | Redakto nëpërmjet kodit]

- Humanism 1: An Outline by Albert Rabil, Jr.

- "Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library & Renaissance Culture: Humanism". The Library of Congress. 2002-07-01

- Paganism in the Renaissance, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Tom Healy, Charles Hope & Evelyn Welch (In Our Time, June 16, 2005)

Referime[Redakto | Redakto nëpërmjet kodit]

- ^ Baku, Pasho, red. (2011). "Humanizëm". Enciklopedia universale e ilustruar. Tiranë: Shtëpia Botuese Bacchus. fq. 425–426. OCLC 734077163.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Mungon ose është bosh parametri|language=(Ndihmë!) - ^ The term la rinascita (rebirth) first appeared, however, in its broad sense in Giorgio Vasari's Vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani (The Lives of the Artists, 1550, revised 1568) Erwin Panofsky. Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art, New York: Harper and Row, 1960. "The term umanista was used in fifteenth-century Italian academic slang to describe a teacher or student of classical literature and the arts associated with it, including that of rhetoric. The English equivalent 'humanist' makes its appearance in the late sixteenth century with a similar meaning. Only in the nineteenth century, however, and probably for the first time in Humanism in Germany in 1809, is the attribute transformed into a substantive: humanism, standing for devotion to the literature of ancient Greece and Rome, and the humane values that may be derived from them" Nicholas Mann "The Origins of Humanism", Cambridge Companion to Humanism, Jill Kraye, editor [Cambridge University Press, 1996], p. 1–2). The term "Middle Ages" for the preceding period separating classical antiquity from its "rebirth" first appears in Latin in 1469 as media tempestas.

- ^ Mann, Nicholas (1996). The Origins of Humanism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–2. The term umanista was used, in fifteenth century Italian academic jargon to describe a teacher or student of classical literature including that of grammar and rhetoric. The English equivalent 'humanist' makes its appearance in the late sixteenth century with a similar meaning. Only in the nineteenth century, however, and probably for the first time in Germany in 1809, is the attribute transformed into a substantive: humanism, standing for devotion to the literature of ancient Greece and Rome, and the humane values that may be derived from them.

- ^ Craig W. Kallendorf, introduction to Humanist Educational Treatises, edited and translated by Craig W. Kallendorf (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London England: The I Tatti Renaissance Library, 2002) p. vii.

- ^ Early Italian humanism, which in many respects continued the grammatical and rhetorical traditions of the Middle Ages, not merely provided the old Trivium with a new and more ambitious name (Studia humanitatis), but also increased its actual scope, content and significance in the curriculum of the schools and universities and in its own extensive literary production. The studia humanitatis excluded logic, but they added to the traditional grammar and rhetoric not only history, Greek, and moral philosophy, but also made poetry, once a sequel of grammar and rhetoric, the most important member of the whole group. (Paul Oskar Kristeller, Renaissance Thought II: Papers on Humanism and the Arts [New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1965], p. 178.)

- ^ Paul Oskar Kristeller Renaissance Thought I, "Humanism and Scholasticism In the Italian Renaissance", Byzantion 17 (1944–45): 346–74. Reprinted in Renaissance Thought (New York: Harper Torchbooks), 1961.

- ^ Giustiniani, Vito. "Homo, Humanus, and the Meanings of Humanism", Journal of the History of Ideas 46 (vol. 2, April – June 1985): 167 – 95. (1) (2) (3)